Written by Chalffy

This is the translated version from a chinese article. Click Here to read the original chinese version.

Leaving Moncuq, my path winding toward a bay in the Basque country.

For Truman Capote, this bay represented the pinnacle of high society, where opulence was saturated with pretentious elegance and unbridled desire, all accompanied by the much-whispered anecdotes of the elite. The Pyrenees stood as a rugged barricade, the vast Atlantic as another limit, while the past and present of this land seemed to blur together in the minds of outsiders—like the legends of famous figures, part gossip, part truth, part invention. At the heart of the bay lies San Sebastián, a city that often emerges from the mist as a place cloaked in a mysterious allure. Its name evokes echoes of Christian defiance, a perpetual waypoint in the literature of the Beat Generation, while today it is hailed in luxury travel media as a haven for creativity and gastronomy. This complex identity fuses the known with the unknowable. Even those who consider themselves versed in the subtleties of Spanish history and culture often find themselves unsettled when they confront the peculiarities of the Basque region and its jewel, San Sebastián. Autonomy, separatism, unity, decay, rebirth, tradition, and innovation—one after another, these themes drain the energy of the people, yet amid the verdant hills and the deep blue waters, they find a place to which they belong.

In the face of grand, insoluble dilemmas, the people of San Sebastián have turned inward, seeking solace and meaning in food, art, and the eternal rhythm of the sea. Accustomed to storms, they still cling to the belief that the sun will rise once more from behind the mountains.

The Ocean – The Sun Rises as Always

At this moment, I am sitting in a café by the sea.

It is the first day of the new year, and for the people of San Sebastián, the sea beside me takes on a different role today—it will cleanse away the anxieties, illnesses, and burdens of the past year. Below the terrace of the café lies the city’s largest swimming club. People, having shed their clothes, emerge in groups from the club, running across the sand and plunging into the sea. The café terrace feels like the balcony of an opera house, with the beach as its stage, where tradition, alongside the yearning for the elegance and prosperity of a city poised between the old and the new, is being performed. The Atlantic rolls its blue and white waves onto the shore, flocks of seagulls swoop past, their cries swallowed by the endless sound of the waves. Their flight is silent, like those black birds flickering across the screen of a black-and-white silent film. A few elderly men, dressed in swimsuits, stroll slowly toward the sea—one clutching a bottle of champagne, the others each holding a glass. It is clear this New Year’s tradition among friends has endured for nearly half a century. Though it is winter, to the people of San Sebastián, it seems as if their city has never truly known winter. The climate here is warm, and the streets are always imbued with a languid excitement—this is a city in constant, simmering anticipation of summer.

The café is named La Concha, after the golden beach that stretches before me. In Spanish, concha means “shell,” and Shell Beach lies nestled between Mount Igueldo and Mount Urgull, two hills that remain green throughout the year, squeezing the beach into a graceful crescent, like the curve of a new moon. I have seen many beautiful beaches, but what sets Shell Beach apart is the space it holds—an expanse filled with the intimate lives of the people of San Sebastián, yet tinged with the luxury of Basque life. In the urban planning of European cities, town squares are often the heart of social life. But in San Sebastián, life revolves around Shell Beach, which faces the open world. In a country where Catholicism forms the bedrock of culture, the people of San Sebastián choose to display their lives openly, under the sunlight. This perhaps explains why the city’s history has been marked by conquest, rebellion, wealth, freedom, and change. The people of San Sebastián are accustomed to being noticed and take pride in the comfort that this attention brings.

It is two in the afternoon, and the nearly two-kilometer-long beach is alive with people. A girl in a turtleneck sweater strolls leisurely with her dog toward Mount Urgull, while elderly men in swimsuits stand waist-deep in the water, raising their glasses in celebration. At their feet, a wave sweeps away a little girl’s sandal. I have seen San Sebastián in the summer; I have seen Shell Beach in the winter. Here, the changing seasons seem irrelevant—people see only the sun, and the blessings the sunlit sea bestows. The promenade along the beach and the city’s main square are equally crowded, the sound of accordions and pianos mingling with the air. Conversations, music, the roar of motorcycles, the crash of waves—all merge into a symphony, with people moving through it only to pause at the railing for a glance at the sea. The view before them is no different from what the gentlemen and ladies of San Sebastián’s golden age once beheld.

Before coming to San Sebastián for the New Year, I had made sure to watch Woody Allen’s latest film, Rifkin’s Festival. Woody Allen had previously filmed in several European cities—Paris with its surreal charm, Rome with its theatrical flair, Barcelona with its vibrant heat. In those places, the character of the city seemed to arise from the depths of human longing and spiritual pursuit. But in San Sebastián, it felt as though the roles were reversed—here, the desires and ambitions of the people seemed to spring from the city’s very essence. In Rifkin’s Festival, nearly every scene that captured the spirit of the place revolved around the sea and La Concha café by the shore. Men and women strolled along the promenade of Shell Beach in the afternoon, plunged naked into the midnight sea, or sat in the café, weaving their conversations around the complexities of relationships. The protagonist’s thoughts wandered between reality and dream along the shoreline. The absurdity of the characters’ lives was heightened by San Sebastián’s own paradoxical blend of the real and the surreal, an artistry born of the city’s dramatic tensions. Whether Woody Allen drew his inspiration from his time at the film festival here is unknown, but as I gazed at the blue-green sea and the hills before me, watching the afternoon mist settle over the seaside theater where the festival took place, and listened to the elderly beside me speak of Godot and Goya—amid the sharp smell of fish and alcohol—I could almost picture the crowds emerging from the theater. After days spent in the dreamlike worlds conjured by cinema, they stepped out to face the hazy yet passionate sea, caught between illusion and reality. Among them, I imagined, was Woody Allen himself. These overlapping scenes of fantasy and reality, like fleeting mirages, seemed to embody the cultural essence of this region by the Bay of Biscay. San Sebastián was such a place, as were Biarritz and Saint-Jean-de-Luz. They all seemed like melancholic, wealthy poets seated by the sea, lost in the contemplation of nothingness.

Just days before, driving from Montcuq to San Sebastián, from sunlight into rain, I had felt this sensation most acutely. For a filmmaker skilled in crafting dreams, San Sebastián provided the perfect stage to draw out the inner lives of his characters.

A sudden scream shattered my thoughts. Between the San Telmo Museum and the Kursaal Auditorium, a wave had surged onto the promenade, drenching those walking along it. Though San Sebastián boasts a broad and well-sheltered harbor, the port narrows sharply into a funnel-shaped river, where wind and waves collide with ferocity, the tides funnelling toward the narrow channel. White spray shot up two or three stories high, rolling through the air as if the people of San Sebastián had poured endless amounts of detergent into the river. Layer upon layer of foam seemed to scrub away the noise and grime of the day, leaving the old town looking as fresh and pristine as ever.

The sunlight began to soften, and the beach before me glowed in a brighter shade of gold. Not far from the Kursaal Auditorium, young people sat along the promenade, legs dangling over the railing, facing the spot where the sun would set—they were waiting for the evening spectacle. By day, Shell Beach opens its arms wide, welcoming everyone who arrives in San Sebastián. But as night approaches and the crowd withdraws to the shore, the sea becomes a playground for the daring. On the rolling waves, the surfers, rising and falling within the white foam, take center stage. Their figures, leaping through the misty air, resemble dolphins. An old man, walking his dog across the sand, paused to watch—was he, in his youth, one of those intrepid souls, once leaping through the waves?

The old and the young, the sea and life. In a city now famous as a holiday destination, San Sebastián remains untouched by the banalities that plague other coastal resorts. At its core is still the rhythm of daily life, and the people of San Sebastián remain the true custodians of their city. Hemingway, in The Sun Also Rises, devoted only a single line to San Sebastián: “Brett came back from San Sebastián.” No further detail was offered, as if every traveler who comes here tacitly agrees that San Sebastián could only exist within this bay, a mirage rising from the sea. Beyond the mountains, at the ocean’s edge, life continues—undisturbed and self-contained.

I walked slowly toward the harbor of the old town. The fading sunlight cast the buildings around the port in deep golden hues before they disappeared into narrow, shadowed alleys. Countless small fishing boats rocked with the sea breeze, their bright colors lighting up the dark hills behind them. The air grew heavy as a mist rose from the sea, transforming Mount Igueldo and the city into the blurred brushstrokes of an ink painting. The cry of seagulls echoed through the fog, mingling with the shouts of boys diving into the dusky sea, the murmured conversations of those waiting for the sunset, and the sharp crash of a tourist’s wine glass breaking against the city walls. The sea was the stage for the lives of the people of San Sebastián, and in the twilight, the old port became the climax of this grand drama. As I turned, the sky had taken on a faint purple-red hue. On the distant breakwater, where the sea stretched into the horizon, fishermen and wanderers stood quietly, their silhouettes outlined against the scattered lights of the city beyond. Beneath the dim glow of the streetlamps, their solitude and stillness appeared all the more romantic. San Sebastián had long grown accustomed to the ebb and flow of crowds, but only in the fading light did its people glimpse their city in its truest form. Any coastal city that once served as a point of conflict, a mediator in the exploration of the world, now shared in this same quietude. Though undercurrents always lingered, there was no contest, no disturbance.

Tomorrow, the sun would rise as it always had, though it was the rain that the people of San Sebastián knew best.

Cuisine – A Table Between Mountains and Sea

The night hung heavy, and the crowds along the shore had dispersed, leaving only the rise and fall of the waves and the flickering of lights swaying across the ink-black surface of the sea.

Yet, the throngs had not truly vanished. They had simply turned their backs on Shell Bay, drawn instead toward the labyrinthine streets of the old town. San Sebastián’s old quarter is neat and orderly, its streets forming a perfect grid, as if laid out with chessboard precision, comforting in their symmetry. I followed the flow of people, walking toward Mount Urgull, and turned into a narrow alley. The passage was exceptionally tight, leading straight to the port beyond the city. Even in the darkness, I could imagine that no sunlight ever graced these streets during the day. On either side, every shop was brimming with life, patrons clutching glasses of wine. A glimpse inside revealed an even denser crowd. These bars and eateries, nestled deep within the old town, lay hidden in the shadows, their facades modest, unadorned save for the name above the door and the proud inscription of a founding year—1892—marking their legacy. These unassuming establishments, weathered by time, had become the foundation of one of Spain’s most beloved culinary traditions. The Basques call them pinchos, though elsewhere in Spain, they are more commonly known as tapas.

A friend had recommended this particular pinchos bar to me many times, and now I found myself pressed against the counter, unable to move in the crush of bodies. These bars share a distinctive layout, intimate in size. A wooden counter occupied nearly half the small space, and behind a glass cover, row upon row of pinchos were displayed: bread topped with foie gras, grilled octopus, prawns, artichokes—each creation held together by a slender skewer, the very origin of their name. In Basque, pincho means a small, pointed object. Behind the counter, five young staff members darted about, balancing white plates in one hand and tongs in the other, trying to decipher the cacophony of demands from the noisy crowd. In this world dominated by the Basque language, the hand gestures of tourists had become a new form of communication.

“Do you need anything?” A server’s voice broke through, his eyes meeting mine briefly, a mix of urgency and curiosity in his expression. He swiftly snatched a plate from behind him, ready for my order.

For most first-time visitors to a pinchos bar, ordering was anything but simple. The counter was crowded with diners lost in conversation, and there was no formal queue. It was a matter of seizing opportunity, slipping into whatever space opened up. The moment a server made eye contact, even for a fleeting second, one had to declare their request immediately. As soon as I accepted the plate, the server’s attention shifted to the person behind me, our interaction disappearing within the span of those brief ten seconds. Yet, amidst the bustling chaos, there was an unspoken rhythm; the crowd instinctively made space for me to eat. In this noisy, animated scene, the least pressing matter of the evening, ironically, was settling the bill.

For the people of San Sebastián, pinchos are more than food. They are a ritual that transcended the plates. Created to accompany conversations between friends and family before the main meal, the act of gathering and socializing far outweighed the act of tasting. A small dish, a glass of red wine—enough to fuel hours of companionship. In this old town, where nearly everyone knows each other, there exists a silent trust between diners and restaurant owners—no one ever left without paying. Though San Sebastián never lacked tourists, its people will never compromise their food for anyone. Every ingredient, every method of preparation, every color, texture, and flavor had to follow tradition, leaving the unmistakable imprint of the Basque spirit.

Through the passage of time, pinchos bars had not become mere fantasies for tourists. Instead, they remained the daily dining and social hubs for locals. Many of these bars, now scattered across the city, had been in business for nearly a century. Even the newer establishments adhered to this legacy of trust passed down through generations. This mutual trust formed the bedrock of a communal life that San Sebastián, and indeed the entire Basque region, held with pride. Just as food was linked by skewers, so too were people connected by food, creating a broader social understanding. In a sense, San Sebastián itself was like a grand pincho, its narrow, unassuming streets like wooden skewers threading together the city’s collective memory and affection.

As midnight approached, the pinchos bars of the old town grew busier still. The locals knew the specialties of each one and, starting at dusk, they wandered through the streets, stepping into whichever bar beckoned. They ordered a signature dish and a glass of wine, perhaps leaning against the bar, perhaps standing in the street. And as their mood lifted, they moved on to the next place. What might seem a simple meal was in fact the ceremony of visiting old friends.

The pride of the Basque people in their independence and unity may, perhaps, have its roots in this very culture of food.

In 2012, San Sebastián was crowned the world’s culinary capital. Reflecting on the reasons behind its triumph, food critic Nina Caplan observed, “Many cities can offer food that meets Michelin standards, but it’s rare to find a place where you can step into any restaurant and trust that three dishes will have flavors like nowhere else.” In this coastal town, less than one percent the size of Shanghai, there are sixteen Michelin-starred restaurants—the highest density in the world. Among them, the globally renowned Arzak and Mugaritz stand as culinary icons. Beyond these bright stars, the city is dotted with Michelin-recommended establishments, so ubiquitous they almost go unnoticed. Whether it’s the traditional fare served at a humble pinchos bar or the bold, inventive creations of a Michelin-starred kitchen, the people of San Sebastián have poured their passion for life into an obsession with food.

To trace the origins of San Sebastián’s culinary excellence, one need only stroll a few paces toward the harbor. The birth of this gastronomic paradise was not a matter of fortune alone—it required a perfect alignment of time, place, and people. Nestled between the Atlantic Ocean and the Eurasian continent, blessed by the bountiful waters of the Bay of Biscay, the sea has been extraordinarily generous to San Sebastián. Red prawns, shellfish, lambs grazing on verdant hills, red peppers, tomatoes—ingredients of the highest caliber, abundant and rich in flavor, have provided local chefs with an unparalleled canvas for their creativity. Even before my arrival in San Sebastián, friends had eagerly recommended various Basque restaurants and dishes, each description tinged with envy and fond nostalgia. These eateries, hidden in the hills, tucked into city streets, or scattered across rural farms, boast global acclaim. Yet, compared to the famed chefs of other Spanish cities, San Sebastián’s culinary masters remain remarkably modest. Take Juan and Elena, the father-daughter duo behind Arzak—despite their restaurant holding three Michelin stars for over thirty years, they quietly labor in the kitchen each day, guardians of color and taste. This generation, who describe themselves as “diligent, meticulous, and restless,” possess a profound understanding of both their craft and the city they inhabit. Through this blend of deep knowledge and insatiable curiosity, the young chefs of San Sebastián continue to expand the city’s culinary legacy.

Art: the Rebirth of a City

Art, too, is a subject that cannot be overlooked in the Basque region.

Even those with little familiarity with contemporary art will have undoubtedly heard of Picasso’s Guernica. This small town, a mere half-hour’s drive from San Sebastián, became a profound symbol of Basque identity when it was bombed—an event that gave birth to one of the world’s most influential works of art, filled with anguish and cruelty. The creation of Guernica, from its inception to completion, remains a subject of fascination in the art world to this day. Coincidence, rejection, sorrow, failure, destruction—all these marked Picasso’s journey in producing the piece. I have stood before it many times in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, in the near silence of an almost empty gallery. The vast white walls, nearly swallowed by the immense painting, with only a listless security guard for company. As the sole object of attention in the room, the expansive space seemed to narrate Guernica’s origins amid the ruins of war, and its transformation into a beacon of future possibilities.

Rebirth—it seems to be one of the most potent themes in Basque art. Yet, to truly grasp this idea, one must venture beyond Guernica to another city not far away.

I drove westward, the rain falling steadily, as road signs indicated that Bilbao was only half an hour ahead.

The sky was churning with thick, dark clouds, casting a deep green hue over the hillsides flanking the road. The hills themselves were unassuming, rolling gently behind me as I pressed forward. Along the slopes, neat farmhouses, their walls painted white, punctuated the landscape. The land was fertile and lush, with cows and sheep grazing freely across the farms. Compared to the opulence of seaside San Sebastián, the Basque highlands appeared far more modest. Yet I knew that within these quiet homes, hidden amid the woods, lay the origins of the Basque culinary tradition. As I scanned the horizon—nothing but greenery and storm clouds ahead—the road stretched unwavering, crossing the plains toward Bilbao.

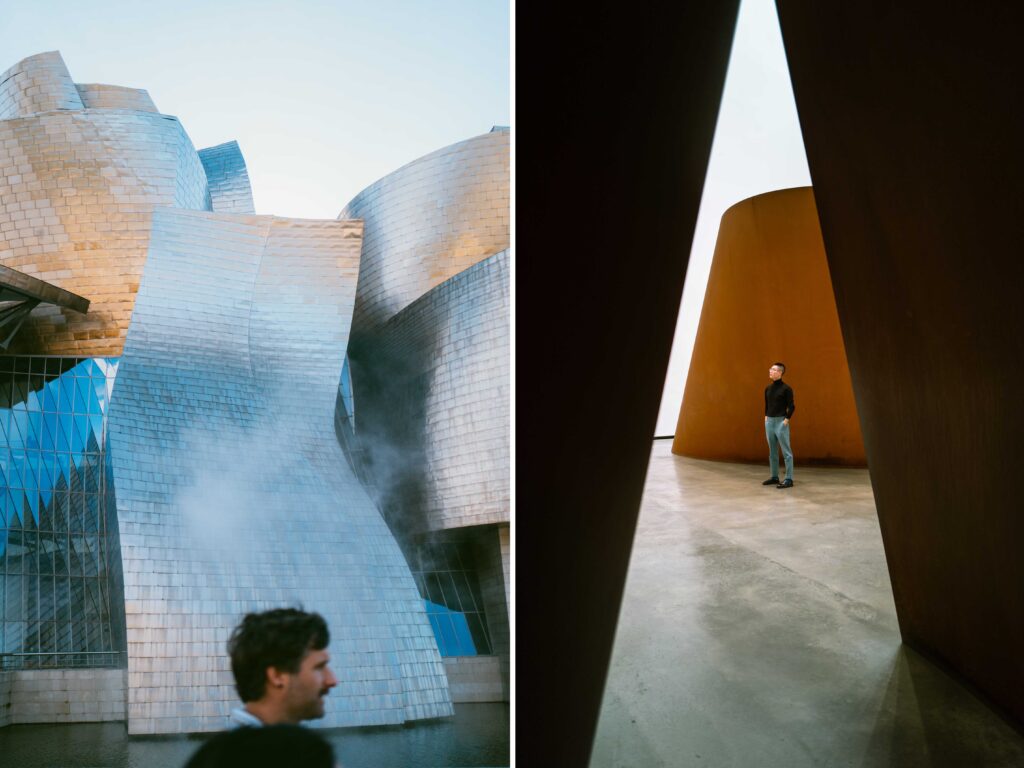

Crossing the La Salve Bridge over the Nervión River, the pastoral scene gave way. The city, with its tall buildings, traffic, and the imposing red arches of the bridge, rose abruptly before me, full of energy. And there, just to the right of the red bridge, stood a metallic structure, twisted and coiled, its entire façade gleaming in the post-rain light like a vision from a science fiction film—the Guggenheim Museum. It was the sole reason for my journey to Bilbao. In fact, the red arches I had just passed were themselves part of the Guggenheim’s architectural design, a testament to how the city had grown around this singular structure. The nearly seamless transition from mountain to city, with no pause for the eye, seemed intentional—a deliberate expression of Bilbao’s own fate. From the brink of decay and oblivion, the city had made a bold, all-or-nothing leap to be reborn as a city of art.

As I approached the Guggenheim Museum, what struck me first was its serpentine form. Facing north, draped in shadows, the building—designed by Frank Gehry—seemed to bend and twist in all directions, a fluid composition of hyperbolic surfaces. Depending on the hour of the day and the angle of the sun, the museum’s walls shifted in color, playing with light in ways that felt almost ethereal. As I drew nearer, the façade transformed—gradually sliding between shades of blue, orange, silver, and black. The metallic panels, like the scales of a great, slumbering dragon, coiled along the riverbank, guarding the city’s future. For an industrial town whose allure had long faded, the Guggenheim breathed life into Bilbao, softening the otherwise heavy, industrial air.

I recalled seeing two photographs—a stark before-and-after comparison of Bilbao, taken from the same vantage point in 1980 and 2018. In the older image, Bilbao lay in steep decline—rebellion, the collapse of the shipbuilding and steel industries, urban pollution, and the terror of bombings had darkened the city’s prospects. The port, in that earlier photo, was desolate and abandoned. But in the newer one, after Bilbao had risked its entire municipal budget to secure the Guggenheim’s European home, green spaces, towering buildings, movement, and vitality filled the frame. Once greeted with doubt, the museum’s rapid success silenced the critics overnight. Within six years, the influx of visitors, drawn by the Guggenheim, had more than repaid the city’s investment. Bilbao, once fading into irrelevance, flourished with new jobs and a vibrant cultural renaissance. A dying city had been reborn, and this transformation became known as the “Guggenheim Effect.”

Inside the museum, the harsh metallic exterior gave way to an explosion of light. A soaring, fifty-meter-high dome bathed the central atrium in natural light. Around me, transparent and opaque materials seemed to alternate whimsically, creating a shifting interplay between illusion and reality. What initially appeared chaotic was, upon closer inspection, a carefully orchestrated harmony. Columns, bridges, and elevators encircled the atrium, weaving together the museum’s nineteen galleries. Each gallery adhered to a similar design principle—vast expanses of emptiness. Glass, limestone, titanium; chaos and order; openness and void—the entire structure evoked the hulking cargo ships that once dominated Bilbao’s docks. In Gehry’s design, there was an homage to Bilbao’s industrial past, but equally, a bold gesture towards the city’s boundless future.

Among the museum’s most prominent exhibits, works by Picasso and the Basque artist Eduardo Chillida commanded attention. Chillida’s sculptures and drawings, in particular, inhabited the galleries with a profound presence, each piece a meditation on different facets of Basque philosophy. Even at the hotel where I stayed in San Sebastián, Chillida’s works—both sculptural and illustrative—adorned the lounge. His metal sculptures dotted the coastline, scattered across the shorelines like sentinels of memory. In many ways, Chillida’s art encapsulated the emotional landscape of the Basque people. His sculptures, forged from wood, stone, and metal, and his stark, black-and-white drawings expressed the central preoccupations of his life’s work: opposition, unity, eternity. At a time when Basque nationalism was surging, his work resonated with multiple interpretations, as viewers projected their own political leanings onto his art. By placing his sculptures across the land—between mountain and sea—the Basque people affirmed their identity, carving out their place in the world through Chillida’s profound and enduring vision.

IIn one of the Guggenheim Museum’s first-floor galleries, Richard Serra’s installation, The Matter of Time, commands attention. This piece, one of the most captivating for visitors after the Spanish works, consists of eight monumental steel sculptures, standing side by side, progressing from simple to increasingly intricate forms—evolving from double ellipses to spirals. To truly experience the installation, one must enter each sculpture, follow the spiral path to its core, and then retrace their steps to move on to the next. The interplay between openness and confinement, between cyclical and linear movement, renders the elusive nature of time into a tangible, spatial experience. The Basques, grappling with their own contradictions—ethnic autonomy, industrial transformation, and questions of identity—seem to regard time as the canvas upon which their answers and explorations are written, seeking meaning through both temporal and artistic realms.

On the plaza near the Nervión River stands Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture, Maman. This towering bronze and marble spider, rising over nine meters high, complements the metallic backdrop of the museum while preserving the memory of the city’s industrial past against the backdrop of green hills and clear waters. Bourgeois’ work embodies a lifetime of maternal yearning, where trauma, pain, and longing are woven into the cold steel of the sculpture—emotions the people of Bilbao know only too well. The spider, with her long, powerful legs rooted in the ground, gazes toward the mountains and the great river, turning her back on the modern city that rises behind her. The sculpture suggests a paradox of protection and rejection, reflecting a subtler, often overlooked aspect of the Basque psyche.

A man jogging beneath the spider’s slender legs vanished into the mist of a nearby water feature, while an elderly couple walked hand in hand, their presence leaving only the faintest trace against the steel. Quiet Bilbao, subdued San Sebastián, both patiently awaited their turn in the tides of time.

Happy New Year

On New Year’s day, San Sebastián basked in sunlight.

As one of Spain’s rainiest regions, a clear New Year’s Day was perhaps the most perfect way for its residents to both conclude and commence the year. People reveled in the sunshine at the century-old amusement park on Mount Igueldo, paid homage to their esteemed tennis stars on the courts below, and were serenaded by melodies mingling with the sounds of the sea and the cries of seagulls. Along the waterfront promenade facing Shell Beach, buildings stood shoulder to shoulder, four or five stories high, their white and cream-yellow facades exuding elegance and nobility. Though the Basque region boasts a profound history, the architecture here is relatively modern, with these seaside buildings being just over a century old. Today, half serve as summer vacation homes for Northern Europeans, while the other half are restaurants and hotels, among which the Hotel Londres and the María Cristina Hotel are particularly renowned.

In Truman Capote’s final novel, Answered Prayers, he approached his subject with unprecedented candor, chronicling the lives and private affairs of a slew of social elites. Many of these stories, rich in high-society gossip, were drawn from a restaurant frequented by Capote and his socialite friends. This restaurant’s name was also the original title intended for the novel: La Côte Basque. For the affluent and the so-called “Beat Generation” of that era, the Basque Bay, including San Sebastián, epitomized European luxury. Today, among the cities of that once-glamorous bay, only San Sebastián has managed to preserve its status of wealth and indulgence through the vicissitudes of time.

For San Sebastián, this is both a blessing and a burden. Amidst the excessive attention and a tranquil, unassuming existence, the locals have found few ways to strike a balance.

For the people of San Sebastián, New Year’s Eve is the second most significant night of the year, surpassed only by Christmas Eve. Families gather for a late dinner, and at the stroke of midnight, they consume twelve grapes, one for each chime of the clock. Following this ritual, they spill into the streets to celebrate through the night.

After dining at the hotel, C and I chose not to partake in the grape-eating ritual with the other guests. Instead, we wandered into the Old Town, heading toward the Old Port. Unlike on other nights, San Sebastián seemed to have shed its usual blend of life and desire, embracing an unusual silence. Shops and restaurants were shuttered, and New Year’s Eve was not a time for serving patrons. As we meandered through the cobblestone streets of the Old Town, the only sounds were the rhythmic clack of our shoes on the stones, the distant murmur of conversations from within nearby houses, and the fleeting rush of pigeons. Even the street lamps seemed dimmer than usual. Only the Church of Our Lady at the end of the alley remained as bright as ever. An elderly couple emerged from a nearby alley and turned a corner, vanishing into the enveloping darkness. After the incessant noise and fervor of San Sebastián, this tranquility felt strangely unsettling.

Above me to the right, warm, yellow light spilled from an apartment onto its balcony. A man sat in an armchair, holding a glass of red wine while speaking on the phone. As I looked up, he noticed C and me walking down the empty street.

“¡Feliz Año!” A cheer arose from behind us. We turned to see the man on the balcony raising his glass in a toast.

“¡Feliz Año!” I replied softly. Happy New Year—surely, this was a universal greeting.

As midnight approached, the area around the Old Port began to fill with people. They gathered in clusters, whispering, reluctant to disturb the rare tranquility. I glanced toward the city below Mount Igueldo, where a solitary flame ascended into the sky, culminating in a muted firework display. Almost simultaneously, the bells of the Church of Our Lady in the Old Town began to toll. The deep tones reverberated through the air, their trembling echoes illuminating the streets and amplifying the crowd’s murmur—San Sebastián’s clamor was reawakening from all directions. Reserved groups exchanged New Year’s wishes, and the sound of champagne corks popping emerged from the darkened seafront promenade.

As one silent firework faded below Mount Igueldo, another ascended to burst above. San Sebastián did not feature a unified New Year’s firework display; instead, these fireworks appeared from various homes and corners of the city. In contrast to grand, exuberant celebrations, these scattered bursts conveyed a warmth of shared joy.

They twinkled like distant stars, serving as beacons of blessing among the people of San Sebastián in the darkness.

Email:chalffy@chalffy.com

Instagram:chalffychan

More Articles here