Driving north from Aswan to Luxor, the entire journey clung closely to the Nile.

Through the right window, children rode donkeys along the roadside. The oasis plains stretched out endlessly, flanked by rows of tall, dense date palms, heavy with ripening fruit. Behind them lay fields of sugarcane and wheat, lush and verdant. Occasionally, a farmer in a white robe would traverse the fields, his dark skin forming a striking contrast against the deep green of the earth and the pristine white of his garments. These scenes, timeless and unchanging, imbued the southern Egyptian countryside with an enduring charm.

The Nile, though occupying a mere 5% of Egypt’s land, sustains 96% of its populace. As the ancient Romans astutely observed, “Egypt is truly just the land along the river.” All energy and vitality coalesce around this slender ribbon of water, meandering through the desert’s vastness. The fervor and competition for its life-giving waters far exceed the river’s modest dimensions. It flows, almost weary, across the arid expanses, its course intimately entwined with the lives of the Egyptians. Along its path, small towns and villages emerge like delicate brushstrokes on a barren canvas of dust and sand. The density of these settlements is such that, over a span of three hours of driving, one might be tempted to think they are witnessing the same town repeatedly. These villages, though seemingly repetitive, resonate with both monotony and vibrancy: tea houses, morning markets, meandering crowds, napping taxi drivers, bakeries, fishermen, stray dogs panting beneath the sun, and congregations gathered outside the mosques.

The great river flows on, and life, in all its myriad forms, endures unceasingly.

As the journey neared Luxor, the Nile gradually widened. The lush oasis farmlands yielded to dune-strewn villages, and the ancient visage of Egypt was gradually supplanted by a more modern face.

In the Luxor region, security checkpoints along the roads became increasingly frequent. Police officers, clutching small booklets, scrutinized vehicles’ interstate permits—I remained perplexed as to why plates from Aswan could not proceed directly into Luxor. They inquired about passengers’ nationalities and, with a casual flick of their pens, permitted passage. Perhaps this was a vestige of the terrorist attacks from thirty years prior. Yet, from the intensity of their vigilance, it seemed to be another historical inertia woven into the fabric of Egyptian life. The scene where the driver had to roll down the window at each checkpoint and proclaim “China!” was yet another of those amusing and unforeseen quirks of everyday Egyptian existence.

Turning onto the Corniche, I arrived at the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor—a place unparalleled in its global archaeological significance. Whether it was the world-shaking discovery of Tutankhamun or the excavations by international teams at the Karnak Temple, the murmurs and updates about these monumental events were first shared in the quiet corners of this hotel.

From the balcony, the ever-expanding Nile bisected the city. The bustling east bank, where the hotel stood, had been the primary residential area since antiquity. The west bank, serene and picturesque, lay enveloped in a misty light, representing the domain of gods and the dead, where much of the ancient Egyptian history’s legends and stories were interred.

A river divided life from death, the present from the afterlife—a phenomenon not unique to other civilizations. Yet, it was the ancient Egyptians who embraced this division with such thoroughness and romance.

Pharaohs Among the Gods

From the map, it was clear that the Luxor Temple was situated merely a few hundred meters from the hotel. Further afield, the illustrious Karnak Temple stood, the two majestic edifices linked by a three-kilometer avenue adorned with ram-headed sphinxes.

As evening descended, I walked towards the Luxor Temple.

Upon entering the vast forecourt of the temple, I was immediately enraptured by its splendor and otherworldliness. The entrance, erected by Ramses II, was marked by towering obelisks that soared nearly twenty meters skyward, their stately forms casting long shadows upon the Nile’s banks. Flanking the entrance were four colossal statues of Ramses II, their imposing figures serving as silent sentinels. The entrance itself, in contrast to the temple’s grandiose exterior, appeared narrow and elongated, leading into a dimly lit interior. Confronted by such magnificence, one could not escape a profound sense of humility. Each day, the ancient Egyptians must have been confronted with these deified pharaohs, their lives a continual interplay between light and darkness, reality and myth, woven into the very fabric of their sacred rituals.

Navigating through the dim, narrow passage, I emerged into a brightly illuminated courtyard. To my right, two rows of immense stone columns stood in solemn alignment; to my left, statues of the pharaohs loomed, their forms shrouded in shadow beneath heavy limestone slabs that delineated the boundary between the mortal and the divine. I cast my gaze upward towards a high structure in the rear left, finding a touch of irony in its form: this edifice, divided into three distinct layers, resembled a historical palimpsest. The ground floor evoked the semblance of an ancient Egyptian temple, the middle layer a Christian church, while the uppermost layer housed a mosque, its minaret piercing the sky. In the span of five millennia, Egyptian history had unfolded in layers: the first three thousand years belonged to the pharaonic temples, the subsequent millennium to the Greco-Roman period, and the final thousand to the Arab-Islamic world. Five thousand years, three faiths, all interred and intertwined in the sands of time. The conquerors of yore yielded to the new, their spiritual worlds merging within the temple’s walls, where the remnants of past devotions found a new, harmonious existence.

As I approached the southern colonnade of the temple, the reliefs above depicted the coronation of Amenhotep III, surrounded by deities in a scene of solemnity and grandeur. Passing through the colonnade, I encountered a hall dedicated to the Roman Emperor, where the altar was flanked by Corinthian columns—an elegant fusion of ancient Greek architectural grace and Egyptian sensibilities. Beyond the altar lay the sanctuary, a space once devoted to housing the shrine of the god Amun. Luxor, once known as Thebes, had been the resplendent capital of ancient Egypt. The sun god Amun was the most venerated deity among both the people and the pharaohs, and the two most celebrated temples in Luxor were dedicated to him. Each year, during the Egyptian New Year, the Luxor Temple played host to the Opet Festival. Statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were transported on a sacred boat from the nearby Karnak Temple to the Luxor Temple, receiving the adoration of the masses along their journey. When a new pharaoh ascended to the throne, this temple served as the sacred meeting place with the sun god.

Temples on earth had become the abodes of gods within the mortal realm.

As the sun set, its golden rays streamed from the western bank of the Nile, casting the stone columns in a resplendent, golden light. In this interplay of light and shadow, the temple assumed an even greater aura of mystery. I looked up, and in the sunlit areas, ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs adorned the columns, testament to the artisans’ and architects’ lifelong dedication etched into these stone pillars. Each symbol might be interpreted individually, yet together they remained shrouded in enigma. For a culture as cloaked in mystique as ancient Egypt, perhaps the modern world’s inability to fully decipher these meanings only enhances its allure.

The evening breeze carried a coolness from the river, and the palm trees swayed gently in the twilight. As the full moon ascended, it appeared to be cradled by the stone statues of the pharaohs. Could this ancient moonlight and evening wind once have listened to the voices of the ancients, singing the inscriptions upon these sacred columns?

Upon emerging from the temple, I found that night had already descended. The intense heat of the day had ebbed, and the square outside the temple, now enveloped in darkness, was alive with people celebrating Eid al-Adha. Time, ever elusive, had transformed the Egyptians of today into a people distinct from those of the temple era. Yet, during festivals, the people of Luxor continued to gather in temples that bore no resemblance to their own belief systems. These celebrations lacked the grandeur of religious and royal ceremonies, leaving only relaxation and enjoyment.

Perhaps it is in such moments of relaxed celebration that the eternal faith of the Pharaohs endures most profoundly.

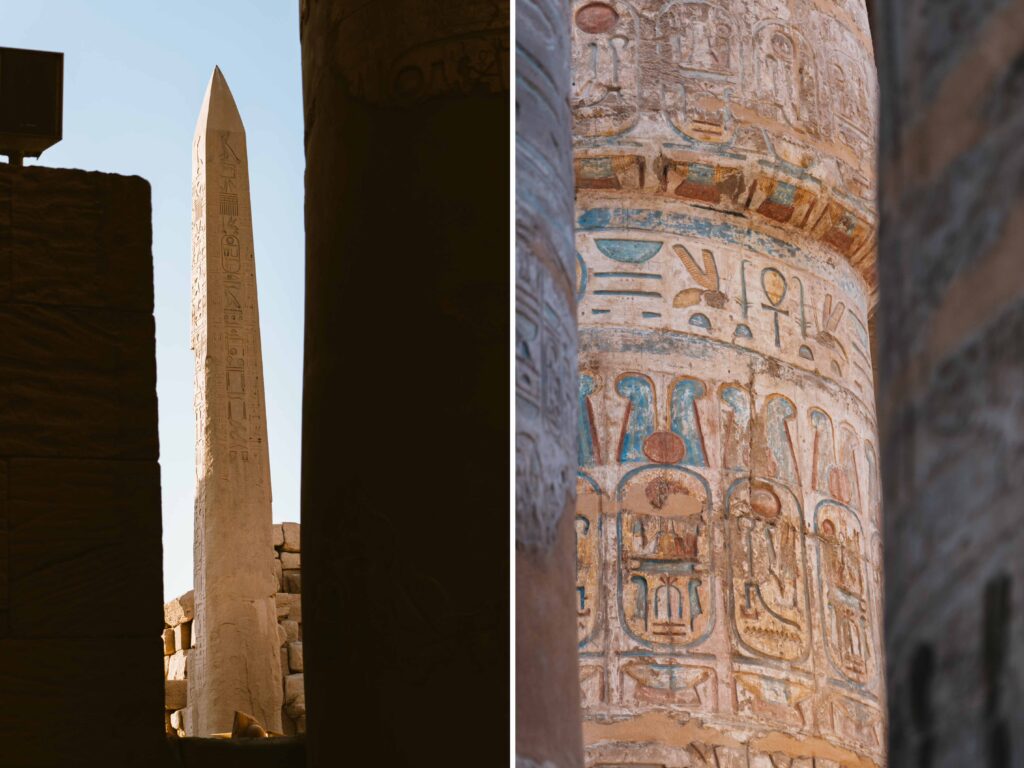

At the entrance of the Luxor Temple, a grand avenue of ram-headed sphinxes extends straight for three kilometers to the Karnak Temple. Karnak closes early, and I had not managed to visit it the previous night. Rising at dawn the next day, I entered the deserted Karnak Temple amidst a golden morning haze.

In stark contrast to the entrance of Luxor Temple, the Karnak Temple appeared overwhelmingly vast and dilapidated, its silent desolation imbuing it with an air of profound antiquity. Gigantic fragments, statues of pharaohs, and the tips of obelisks of various sizes seemed to converge chaotically within my field of vision, leaving me somewhat dazzled.

If ancient Thebes in Luxor symbolized the zenith of Egypt’s history, then Karnak Temple was the brightest star in that celestial expanse, embodying the modern Luxor. Each generation of Pharaohs entrusted their lives, worries, and hopes to this forest of colossal stones. They expanded it in concentric circles, erecting monument after monument, and upon land surpassing half the size of Manhattan, they bestowed the finest of ancient Egyptian craftsmanship upon the earth. To this day, Karnak Temple remains the largest open-air museum on the planet.

Its most captivating feature, the one that has bewitched the world, is the temple’s hall of columns—a spectacle as magnificent as a primeval forest and the marvel I most anticipated in Luxor.

Within less than a hundred meters of entering the temple, the grand hall revealed itself to me. One hundred thirty-four columns, each reaching twenty-one meters in height, stood in orderly rows on either side, glowing with a pink hue in the morning light. The central columns near the aisle were more robust, reputedly capable of accommodating nearly a hundred people standing shoulder to shoulder. The decorations at the base of the columns had mostly succumbed to the ravages of time, while those nearer the top were better preserved. Looking up, the ancient Egyptian motifs near the summit still retained their vibrant colors. This hue rendered the representations of birds, insects, fish, and people more vividly animated, cleverly balancing the solemnity of the columned hall. Scholars have speculated that these towering columns were intended to facilitate the Pharaoh’s communication with the heavens. If this were true, then these images, densely etched with representations of all things in existence, would transform communication into a collective chant of creation. The intricate patterns that adorned the columns rendered the colonnades of ancient Greece, Rome, and China almost insignificant by comparison.

As I wandered among the columns, the sunlight gradually dimmed. In the intermittent chirping of birds, I felt the profound mystique and weight of divine kingship. The colossal images were awe-inspiring, and in the presence of such material grandeur, the human spirit felt diminutive. This humility underscored the ancient reverence for royal power.

Atop the columns were open papyrus flower shapes. Papyrus, the earliest writing material used by humans, was crafted from reeds along the banks of the Nile. Only through the medium of papyrus could words and civilization be preserved. These flowering columns upheld a fragment of civilization’s eternity in history.

Above the columns rested massive limestone slabs. How were they placed there? Was their purpose merely to provide support, or did they carry deeper meanings? The ancient Egyptians left too many questions unanswered, leaving us today with nothing but a sigh of wonder.

May You ALWAYS See the Beauty

On the way to the Valley of the Kings on the west bank, the fields along the Nile were already bustling with farmers beginning their day in the morning light. Thanks to the river’s life-giving waters, the Egyptians harvested abundance from the boundless desert. The fields before me, nestled in the narrow strip between the Valley of the Kings and the Nile, had been transformed from a realm once associated with death and the afterlife into a symbol of renewal and plenty.

As we approached the Valley of the Kings, the landscape was dominated by rugged cliffs and barren desert. Scattered colorfully among the hills were mud-brick houses; the driver explained that these were the resolute residents of the Valley. Their ancestors had lived there for generations, facing the rising sun each day and resolutely refusing the Egyptian government’s offer to relocate them to the city. It was a desolate place indeed. Yet, within this seemingly lifeless area lay the brilliant splendor and legends of ancient Egyptian art. During the New Kingdom, the pharaohs’ tombs were hewn from the mountains, their layout dictated by the rock formations. Unlike the towering pyramids of the Old Kingdom, these tombs were buried deep within the desert sands. While the artistic forms of ancient Egypt might seem static, its culture and aesthetics were remarkably adaptable, connecting with the heavens or vanishing into the dust. On this narrow stretch of ancient land, sixty-three tombs of pharaohs and nobles had been discovered.

A shuttle bus was required to travel from the ticket office to the nearest tomb entrance. As I disembarked, the driver called out loudly, “Friend, lend me a hand in buying a car!” Such pleas were frequent during my time in Luxor. Whether in markets or tombs, modern Egyptians living on what was once royal land seemed less concerned with the spirit and civilization of the place. Their immediate concerns were more pressing, such as acquiring a new vehicle.

The undulating, barren hills were devoid of vegetation. Sunlight spilled indiscriminately over the land, rendering everything starkly white. At the foot of the mountains, I could see sporadic cave entrances, resembling deep, dark eyes in the blinding sunlight, exuding a faint air of gloom—these were the entrances to the tombs. In the 19th century, Westerners embarked on a near-mad scramble for Egyptian artifacts, and these tombs had already suffered extensive theft over the ages, with few escaping unscathed. The tomb entrances, prominently positioned in the valley, were not difficult to find. Howard Carter once described these desolate tombs in his diary: “It was a place haunted by ghosts, a hollow necropolis left behind after being looted, with some entrances open, becoming nests for jackals, owls, and swarms of bats.”

The crowd dispersed into various caves, each person eager to seek their own impression of Egypt within the darkness.

Not far from the main entrance, on a stretch of sand and stone, I spotted the number I had been searching for: 62. There, at the entrance to the cave, a black-framed wooden sign clearly read, “Tomb of Tutankhamun.” As I stepped into the cave, a profound darkness enveloped me.

The passage leading to the burial chamber was narrow and deep, with a vertical drop of nearly ten meters, connected by only a slender wooden ladder. The further I descended, the more oppressive and confined it became. At the end of the passage, a dimly lit burial chamber came into view. Compared to the grandeur of the other tombs I had visited, this chamber appeared rather modest, lacking the imposing majesty one might expect from a pharaoh’s final resting place.

The chamber was divided into upper and lower sections. Near the entrance, the walls were bare, consisting only of rough, unadorned clay. Against one wall stood a glass case—within it lay the mummy of Tutankhamun. He appeared diminutive, wrapped in a modest shroud of linen that revealed only his head, neck, and feet. His body, charred black, lay there with a slightly open mouth. The legendary young pharaoh lay quietly before me, devoid of opulent garments or jewels, merely a humble human form.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb embodies every romantic fantasy of ancient archaeology: tombs, adventures, treasures, and curses. It emerged fortuitously at the final moment of an archaeologist’s dwindling funds, buried deep beneath three thousand years of debris. The secretive and cramped chamber was filled with a dazzling array of gold and silver treasures, as if frozen at the moment the tomb was sealed three millennia ago. I had read Howard Carter’s diaries documenting the discovery, filled with his excitement, elation, solemnity, sanctity, fear, and anxiety. As the only tomb in the Valley of the Kings that had not been plundered, this small chamber contained nearly a hundred thousand items, from ceremonial tools to everyday utensils, each a testament to the pinnacle of ancient Egyptian craftsmanship. Today, these treasures are housed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum, attracting countless visitors. Indeed, the fervor for Egyptian archaeology reached its zenith with the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

He emerged from the depths of antiquity, stirring a great wave in the modern world.

The guardian pointed to the mummy’s feet, where clear signs of disease were evident on the left foot. Since the tomb’s discovery, every advancement in medical scanning technology has first been applied to examine this young pharaoh. Was he truly disabled? What were the origins of the tumors in his brain? What was his health like during his lifetime? The world is filled with immense curiosity and enthusiasm about him. Without definitive evidence, all interpretations remain steeped in romantic speculation. We know only that he was crowned at nine and died suddenly at nineteen, his name later erased from history by subsequent pharaohs, leaving behind a series of enigmas.

The pharaoh who made the greatest contribution to Egyptian archaeology had, for a long time, vanished from the annals of Egypt’s history.

I descended to the bottom of the burial chamber, where Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus remained, square and unadorned. The chamber itself was exceptionally small, roughly the size of the two sarcophagi it housed. The walls were covered with frescoes depicting the mummification rites, the goddess Nut’s welcome, and Tutankhamun’s journey to the god Osiris. On the left wall, twelve squares each held a crouching baboon, representing the twelve hours of the night. Compared to the opulence of other royal tombs, these frescoes appeared stark and hurried. Having died young, his tomb was far from complete, and the artisans could only hastily finish their work before the funeral.

As I gazed at the tomb before me, it was difficult to reconcile its modesty with the grandeur of Tutankhamun’s name. From the moment of its discovery to the present, this name has transcended the historical figure, becoming the focal point for the world’s most romantic imaginings of ancient Egypt—a confluence of art and aesthetics from Egypt’s five thousand years of history. Tutankhamun’s era was the zenith of ancient Egyptian history; he deserved a grander tomb, more magnificent adornments. Yet he had only this small, hastily prepared resting place.

Exiting the tomb, I could not help but feel a pang of melancholy. In the smallest of tombs, we had uncovered the greatest archaeological find of Egypt; the youngest of pharaohs had left the world with the most legendary exotic imaginations. Everything about him is imbued with humanity’s quest for love, faith, and myth. Thus, the artifacts discovered in the tomb no longer merely represent the grand and elusive concept of ancient Egypt; they are intimately tied to Tutankhamun, narrating a story solely about his own life.

recalled a snowflake-shaped chalice found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, inscribed with the words: “May you live a million years, a person who loves Thebes and dwells in Thebes. May you face the north wind, and may your eyes see beautiful places.”

Each morning, I liked to stand on the balcony and gaze at the Nile. Hot air balloons ascended from the valley, their flames dancing in the morning light, filling the air with vibrant energy amidst the silence. Occasionally, triangular sailboats glided across the Nile, their sails rippling gently with the current. Thebes had once been the most magnificent city on earth, excelling in art, science, faith, and agriculture along the banks of this grand river. In a sense, all the splendor of ancient Egypt was a gift from the Nile.

Now, everything lay tranquil and silent. On the riverbank, an old man gazed at the village on the west bank in the morning light. Was he awaiting another gift from the Nile? From south to north, modern people along the river continue to entrust their beliefs, loves, and lives to this ever-flowing river. Yet, no one knows what the next gift will be or when it will arrive.