My first impression of Egypt was not of its towering pyramids, nor the vast and enigmatic temples, but rather a hazy, golden tableau: the triangular sails of feluccas gliding gracefully across the deep blue Nile, while slender date palms swayed gently on both banks, and golden dunes stood in silent contrast to the great river. The Nile, having raced from the heart of Africa, carved its way through dense forests, crossed high plateaus, and passed through the driest land on Earth—the Sahara—before at last spilling into the sea. Along its six-thousand-kilometer journey, the river had become a narrow, winding thread in the desert, until it rushed northward, unfurling into a vast delta in Egypt. From above, it resembled a ginkgo leaf.

Modern Egyptian life and civilization have gathered mostly at the tip of this ginkgo leaf, while the slender stem of the river is often overlooked. Too narrow, too modest in its dimensions to have fostered the birth of a great civilization, and yet it was along this very stem—the narrow banks of the Nile—that some of the most resounding names in human history arose: Aswan, Luxor, Tutankhamun, Amenhotep, Ramses… The arid air seemed to hold within it an ancient, enduring power, capable of rendering legends eternal, leaving them undisturbed, scattered across the yellow sands.

Flying from Cairo to Aswan, the shifting landscapes below mirrored the drama of Egyptian life: the line dividing the fertile delta from the desert was sharp, a boundary between life and desolation. Green fields vanished from sight, replaced by the endless stretch of desert, where the earth met the sky in a haze of rising sand. Through this vast yellow sea, the slender Nile wound like a turquoise necklace adorning the throat of a pharaoh. Here and there, clusters of green oases flickered in the barren expanse, solitary and fragile, fleeting against the harsh landscape. I could not help but wonder how, in such an unforgiving land, the radiant civilization of ancient Egypt had flourished so brilliantly.

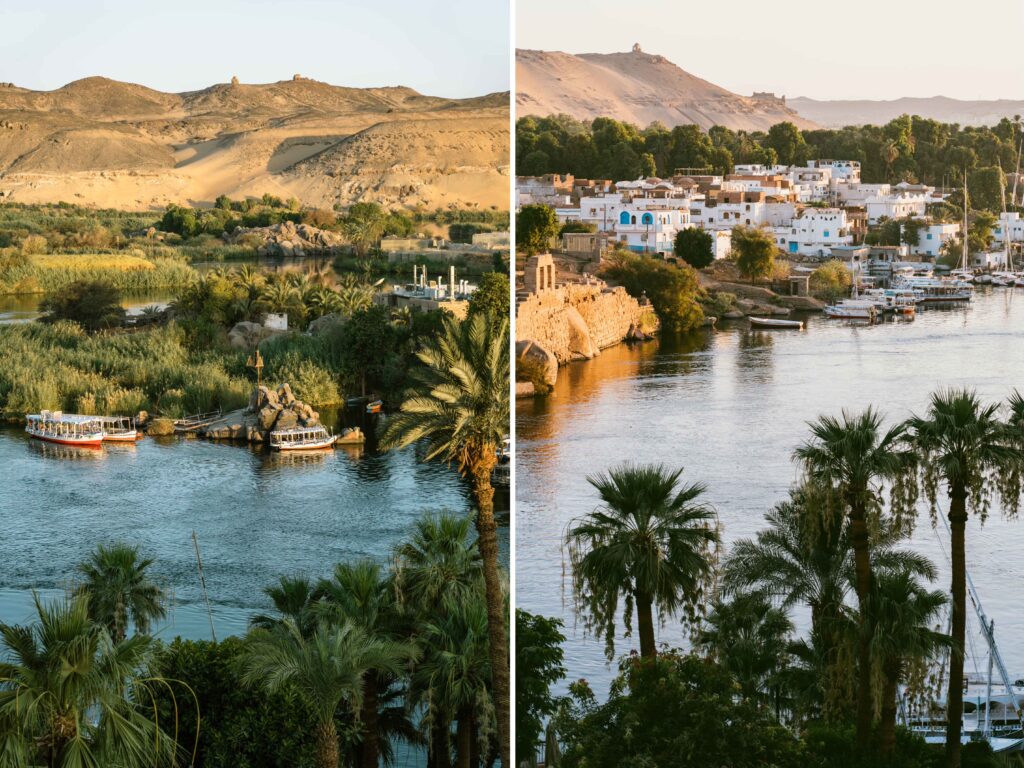

As the plane descended and the river widened, dense reeds swayed along its banks, evoking the serene beauty of southern China’s rivers, where sandbanks and clear waters cradle flocks of birds. The Nile spread swiftly, broadening into a vast blue lake. Between the airport and the river, the Aswan High Dam rose proudly, a symbol of modern Egypt’s ambition.

“Welcome to Aswan!” The driver greeted me with a shy smile. “You’re my first guest from China.” He pointed silently toward the distant dam, his face dark and sharply defined, like an ancient statue carved from stone.

Compared to the almost frenetic pulse of Cairo, Aswan held a quiet, gentle grace.

The Felucca on the Nile

It was near sunset. I sat at the cliffside bar by the hotel pool, sipping mint tea. The golden light of the setting sun bathed Elephantine Island in the middle of the river, while the feluccas on the Nile glimmered with a brilliant white sheen. Their masts stood tall, with sails large and full, disproportionately grand against the slender frames of the vessels. It is said that the English word “skyscraper” was first used to describe the towering sails of these Nile feluccas. They soared so high, it seemed as though they could touch the sky. Indeed, the earliest triangular-sailed boats came from ancient Egypt. On a clay pot unearthed in Nagada, dating back to 3100 BC, one can clearly see a felucca with its tall mast and sails woven from palm leaves.

Today, these exotic boats no longer serve a practical purpose on the Nile. They have become symbols, carrying the dreams of tourists who long for ancient Egyptian civilization—ornaments of pure beauty, drifting on the river.

A felucca, its mast swaying gently, drifted closer to where I sat. Glancing down, I saw a father and son aboard, gazing up at me. “Sir, would you like a ride?” they asked. I had not been particularly interested in a river tour, but under the golden sunset, the grace of the boats gliding over the water beckoned me. Before I realized it, I found myself standing at the dock.

We quickly agreed on a price for an hour’s sail. In Aswan, as in Luxor, there seemed to be no fixed price for services offered to tourists. Both sides carried an invisible scale, and the moment of shared smiles signaled that the balance had been struck. Perhaps they had not expected a customer, for after I boarded, father and son hurried about with sudden purpose. The boy leapt from the shore onto the bow, hauling two enormous cushions, which he spread out with swift efficiency. Then, he climbed the mast to untie the ropes. His father, small and slight beneath the towering sail, struggled to hoist it, each movement labored, his figure dwarfed by the great canvas. After securing the sail, he set two wooden oars at the front and called out loudly to a motorboat on the river for assistance. The felucca had no engine—its motion relied entirely on wind and current, and the initial push from the dock required the help of a modern boat.

Once we reached a patch of reeds in the middle of the river, the motorboat left us, and we sailed forward, carried by the wind. Without the roar of the engine, the Nile was now serene, almost otherworldly in its quietude. The father stood at the bow, gently adjusting the sail to catch the breeze. His movements, once strained, had become fluid, effortless, as if even the sound of his steps might disrupt the rare stillness. The boy sat at the stern, watching his father intently, ready to shift the oar as the sail turned. The water rippled softly beneath us, the shadow of the sail flickering over its surface as we glided through the reeds. It was hard to believe that just beyond this calm scene lay the boundless, barren desert.

The fading sunlight turned the Nile’s waters into a soft purple. Now and then, fishermen from Aswan paddled by in small boats, nodding slightly before vanishing into the reeds. Beside me, the smooth granite boulders of Elephantine Island, polished by the river’s ceaseless flow, stood timeless. The ruins of a temple on the island had become a sanctuary for stray dogs, bathed in the gentle interplay of sunlight and water, radiating a sense of romance and tranquility. On one side, the golden desert stretched away, a line of dense date palms marking the divide between the yellow sands and the blue waves. On the other, a village nestled into rocky hills glowed in the fading light, its pink houses blending with the earth. Life seemed to hide in the folds of the landscape. In the river, boys played in the water while their companions lounged lazily beneath a tree on the bank, perfectly at ease with the world.

Every turn of the boat revealed a new scene, each more beautiful than the last.

In ancient times, Aswan lay near the first cataract of the Nile, a natural barrier that marked the boundary between Egypt and the kingdom of Nubia. But the proud empire of Egypt was never content to be confined by a mere waterfall. The two lands tangled, collided, merged, and parted, with Nubia becoming the source of Egypt’s gold, ivory, and spices, while Egypt became the object of Nubia’s desire and its lifeline. Today, the kingdom of Nubia is long divided between Egypt and Sudan, with most Nubians in Egypt settled here in Aswan. Modern dams have tamed the once-treacherous cataracts, but they have also submerged the relics and history of ancient Nubia beneath the waters.

As we sailed downstream, I noticed the currents swirling in quiet eddies across the river’s surface. The boatman told me these came from the old Aswan Dam nearby, where the once placid Nile now hid its dangers beneath a veil of calm.

“Are you still in school?” I asked the boy, who looked about ten, his bronze face illuminated by bright, eager eyes.

“Yes, he is,” the father answered quickly, pride swelling in his voice. In Egypt’s harsh economy, many children never have the chance for an education. They are seen daily weaving through lines of traffic on busy roads or lingering outside restaurants crowded with tourists. Whether begging or selling small trinkets, their lives often reflect a hardship far beyond what most can imagine. For this young father, keeping his son in school was a triumph, a point of pride in a world where such dreams are often left unrealized.

The felucca moved slowly, driven only by the wind and the oars. We had been sailing for nearly forty minutes, yet the hotel dock remained no more than two hundred meters behind us. Turning the boat around would mean sailing against the wind, and once again, father and son were bustling with activity. My earlier sense of calm gave way to a subtle tension. I thought of the pyramids and obelisks of ancient Egypt, their stone quarried from these very banks, transported north by boats like this one. The ancient Egyptians, advancing at the slowest pace, left behind the most monumental marks of civilization. How they managed to construct such vast structures at such a deliberate speed is still debated by archaeologists today, but I could imagine the Nile in those times—filled with thousands of feluccas, their sails touching the desert winds, carrying the wisdom and craftsmanship that would echo through the ages. They sailed in unison, bound by the sand and the reeds swaying along the riverbanks, their laborious songs passing down a legacy of eternal knowledge and skill.

Across the vast plains and endless skies, one could feel both the grandeur and the melancholy of an ancient civilization.

As the sun cast its final rays over the sand dunes, I stood on the shore, waving goodbye to the father and son. The soft rustle of date palms followed them as they sailed home. One day, when this boy leaves these shores, he too will carry with him the memory of the Nile at dusk, and the ancient winds that have swept across its waters for millennia.

Philae: The Temple in the Water

The day I arrived in Aswan, I caught a fleeting glimpse of the silhouette of the Temple of Philae from the road between the airport and the hotel. It rested quietly on a small island in the lake, its yellow stone blending seamlessly with the surrounding desert. Without any explanation, I already knew its name.

Perched on its island, Philae can only be reached by ferry. At dawn, the air at the pier was crystal clear, and the surface of Lake Nasser shimmered like turquoise. Vendors had already spread their wares on the ground—plastic statues of Egyptian gods and pharaohs, undoubtedly imported from Yiwu, China. A long line of ferries clung to the dock, and with every few steps I took, a boatman would call out, “Yes?”

Massive, reddish cliffs loomed ominously over the lake, their shadows lending a sense of precariousness to the journey. Beyond the lake rose the New Aswan Dam. The temple, once situated on the original Philae Island, had spent decades submerged beneath the water. When the dam’s reservoir threatened to engulf it completely, the Egyptians, with international help, disassembled the temple stone by stone and moved it to Agilkia Island, 500 meters from its original site. There, it was carefully reconstructed, and in 1980, the Temple of Philae was unveiled to the world once more. I had seen a photograph of the temple half-submerged: a Nubian man, dressed in a long robe, rowed his boat through the grand entrance. At first, I assumed the temple had been designed that way—as if to use water and inaccessibility to deepen the reverence for the gods. Little did I realize that even the gods, in the hands of modern engineers, could be so fragile—that divine beings, guardians of humanity, could also require the aid of mere mortals.

Beyond the island, date palms reflected on the surface of the lake, and a gentle breeze carried with it the scent of water and sand. The temple loomed ahead, grand yet serene, its presence as graceful as the goddess to whom it was dedicated.

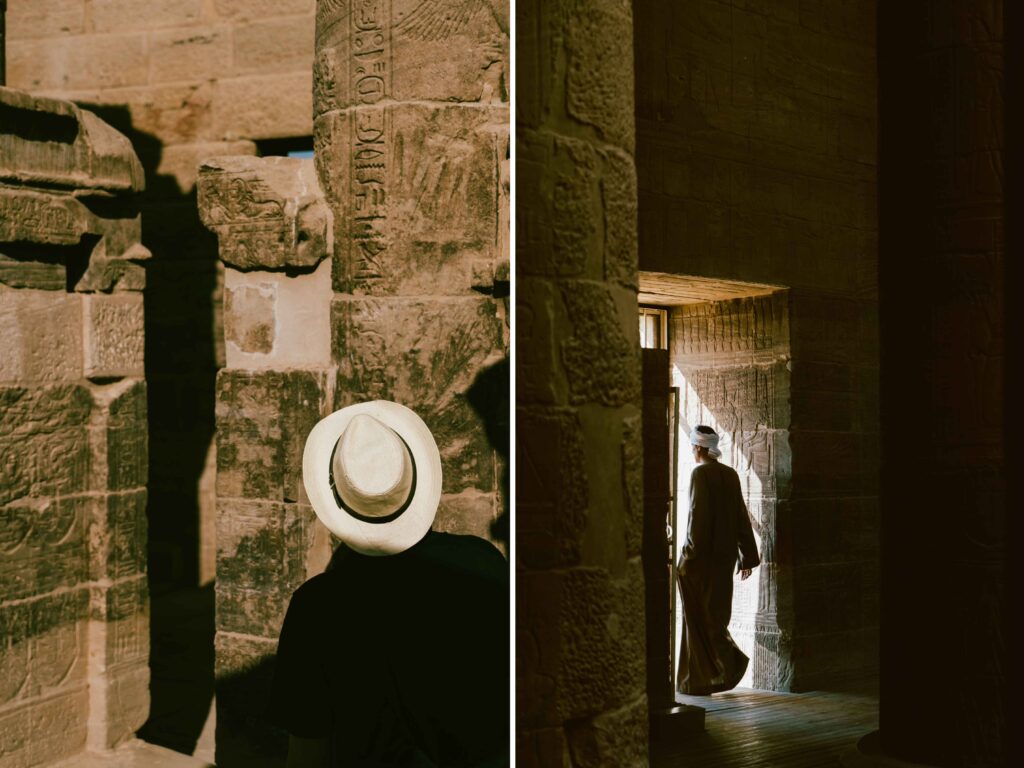

As I stepped into the temple, rows of columns gradually revealed themselves. Alongside the familiar papyrus-shaped pillars stood colonnades reflecting the influence of ancient Greece. The Temple of Philae was constructed between the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, during the reign of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty. Greek culture had seeped into Egyptian soil, while Egyptian iconography found its way into Hellenistic lands. It was a time when human artistic expression entered a new era. The temple was dedicated to the goddess Isis, revered as the ideal mother and wife, the protector of nature and magic. She was one of the most beloved and widely worshiped deities in all of ancient Egyptian mythology. Even as the Ptolemaic dynasty neared its end, Cleopatra—whom the Romans would later call the “Queen of Egypt”—likened herself to the goddess Isis. Of Greek descent, Cleopatra would dress in the likeness of the Egyptian goddess, a choice that added to the legend and enigma of her life.

I stood in the vast courtyard before the temple’s main sanctuary, my feet upon worn, sprawling stones. Rows of towering columns flanked me on either side, while the imposing pylon gate loomed ahead. Yet under the gentle reflection of the lake’s waters, the temple seemed to relinquish any sense of grand authority. It appeared graceful, almost humble. On the walls to the left and right of the first pylon, carvings showed Ptolemy I offering sacrifices to the goddess Isis and the goddess Hathor. Although Isis is often portrayed as the ideal wife and mother, she is also a sorceress in the myths, filled with ambition and intrigue. Her mastery of magic made her the most powerful deity in Egypt’s temples during the period of Greek rule. Magic lay at the heart of her mythology, and in this realm, she surpassed all other Egyptian gods.

I raised my eyes to the top of the columns, where the capitals bore the face of the goddess, gazing out in all four directions. On closer inspection, I noticed the upper parts of the columns were darker, while the lower sections grew progressively lighter. This stark contrast marked the waterline, a silent trace of where the temple had once been submerged.

Inside the temple, the walls were adorned with intricate carvings and hieroglyphs, symbols of human aspiration, the reliefs capturing the intersection of the mortal and divine realms. Though they depicted sacred narratives, the figures of the gods were drawn from Egypt’s everyday life—regal and graceful, their fur-lined garments rendered with meticulous detail.

Standing before these carvings, I felt as if I could hear the gods in quiet conversation, as if I could see the ancient Egyptians striving for elegance and beauty in their every gesture. It was their love for life, their quest for inner truth, that resonated through these images. The ancient Egyptians had bestowed their finest virtues upon Isis, and in doing so, they enshrined those ideals within the temple’s very stones. Remarkably, those millennia-old dreams had not been lost to the encroaching waters.

By the lake, Nubian men in long robes occasionally passed by, moving silently through the temple, their figures emerging from the light only to vanish again into the shade of the columns and trees. Here, there was nothing but the ancient and the eternal, the transparent and the serene.

Checking into the Hotel from Death on the Nile

Before boarding the Karnak, Hercule Poirot and the others gathered at a hotel by the Nile. In the 1978 version of Death on the Nile, I vividly recall the scene: as the Karnak pulled away from the dock, gentlemen and ladies in elegant attire waved their farewells from the hotel pier. Their gestures were not just a send-off for the characters, but seemed to invite the audience into their world. Behind them, under the dappled shade of palm trees, a pink Victorian building gleamed in the sunlight, resembling a palace. While the rest of Egypt languished beneath a veil of desert dust, this palace in its oasis by the Nile seemed surreal, dreamlike, and utterly intoxicating. It was, too, my first impression of Egypt in childhood—elegant and fantastical.

That hotel was the Old Cataract, nestled between the ancient southern frontier of Egypt at the first cataract and the Nubian desert. Established in 1899 by Thomas Cook, it quickly became a favored retreat for Western aristocrats during the British colonial period in Egypt, symbolizing the intense fantasy of Oriental adventure. When Agatha Christie arrived at the Old Cataract, she stayed for many years. The desert, the oasis, the Nile, the hotel—these exotic elements fused in her imagination, becoming the setting for Death on the Nile. With the original film shot on location here, the hotel was thrust once again into global fame. Over the course of a century, it bore witness to major archaeological discoveries in Egypt’s south, hosted royalty from across the world, and stood quietly at the center of history’s unfolding drama.

During my days in Aswan, each morning I awoke to a view from the hotel balcony: dawn’s light illuminating Elephantine Island, where the temples glowed with a golden hue. The Nile, smooth as sapphire, shimmered beneath the white sails, carried gracefully by the wind, while the palm trees lent an air of Oriental mystery. Beyond it all, the Nubian desert rose shrouded in white mist, the pure yellows and blues blending as though heaven and earth were entwined in an Egyptian myth.

“I don’t understand. Why do people live in the past? Why cling to things that are gone?” Tim queries in Death on the Nile. Yet, were he to step beyond his role and absorb his surroundings, the answer might become evident: the old-world elegance, the manners, the strict dress code of the 1902 restaurant, the unchanging desert and oasis… The Old Cataract has never yielded to the pressures of modernity. It remains ensconced in its southern desert oasis, where time seems to lose all meaning, and a millennium passes as effortlessly as the river’s flow.

At sunset, I would find solace in a quiet corner by the river, watching as the light gently faded behind the dunes. The great river lay in silence, boats swaying gently, and the moonlight scattered into a thousand glittering ripples.

Aswan rarely seeks the limelight; it often plays second fiddle to nearby Luxor. Yet on the proud banks of the Nile, its quiet humility completes it. It is like a jewel, hanging low at the southern tip of the Nile, heavy with the weight of time.